What 30 years of whale research tells us about the power of using evidence-based science for conservation management and policy.

by Claire Charlton, Senior Scientist / Director, Current Environment

For almost twenty years, I have migrated each winter to the Head of the Bight, on the vast Nullarbor Plain within the Yalata Indigenous Protected Area.

Each year, I stand on the 50-metre-high Bunda Cliffs, staring south towards Antarctica. I feel the salt spray on my face and breathe in the clean air of the Southern Ocean. I hear a “whoomph” and I look down.

A whale exhales.

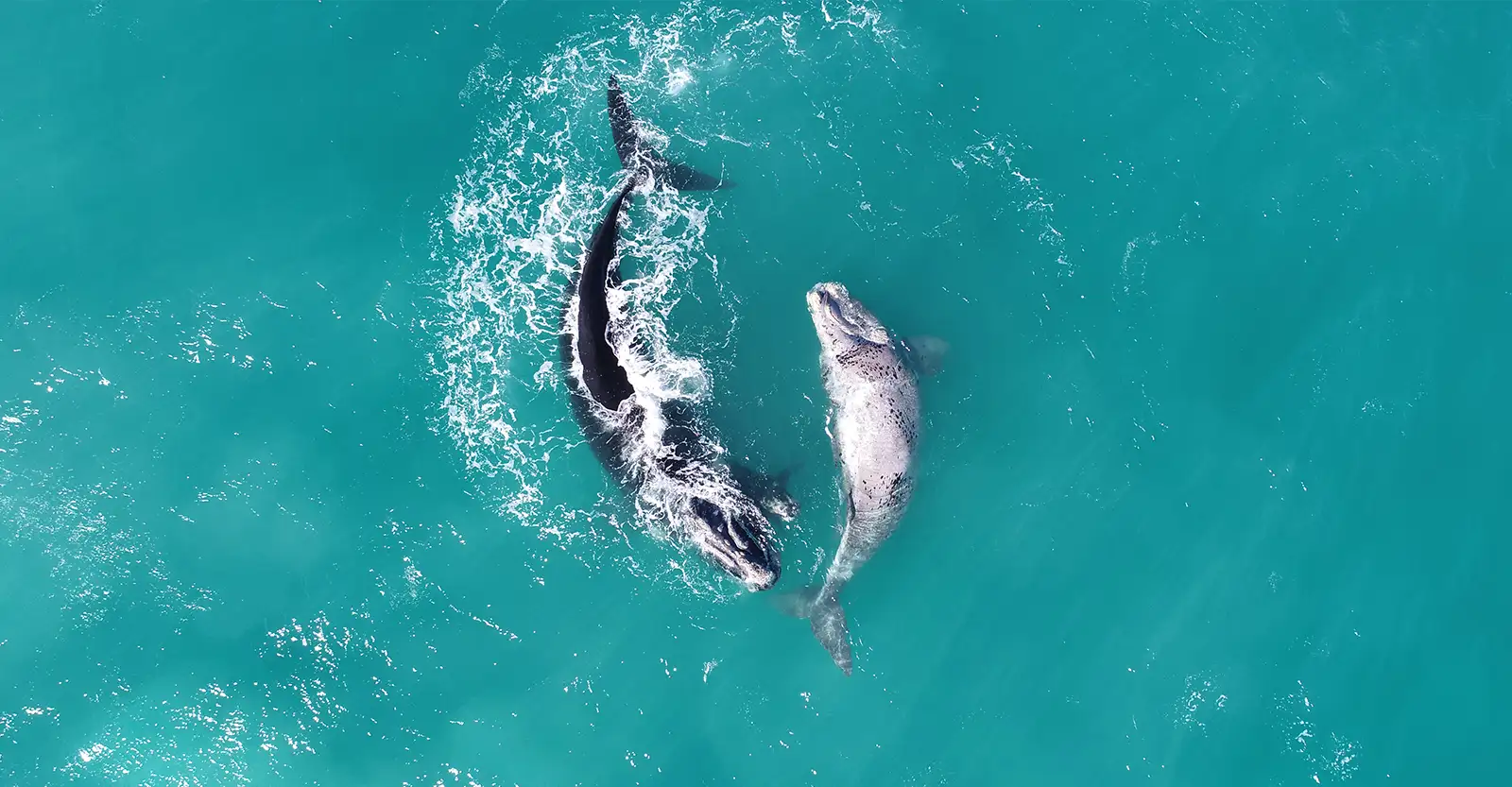

Below me, under the ochre limestone cliffs in clear blue water, a southern right whale mother and her calf rest quietly.

The mother rolls gently on her sides and, for a brief moment, I see her eye. I recognise her. I have seen her before, across years, across seasons. I know her history, her calving record, her movements through time.

I sometimes wonder if she recognises me.

In that moment, I feel deeply connected – to the land and sea Country of the Far West Aboriginal peoples, to the whales themselves, and to the generations of people who have cared for this place. I feel privileged to know these animals. And I feel a responsibility: to speak on behalf of whales that cannot speak for themselves.

I was sixteen the first time I stood on the edge of the Bunda Cliffs.

My mum had driven thirteen hours from Adelaide to bring me to the Head of Bight, Yalata – a spectacular landscape and a coastline that has since etched into my soul. The bay was full of whales. I could see ten, twenty at a time.

Southern right whales drifted through the calm waters – mothers and calves breathing, resting, lingering close to shore. They were so close I stepped back to fit them fully into my camera frame, close enough to feel as though I could almost reach out and touch them.

But it wasn’t only the whales that held my attention.

My focus was on the research team on the boardwalk – cameras ready, notebooks in hand, quietly observing.

In that moment, something clicked. I knew, deeply, that this was what I wanted to do. I wanted to understand the whales. And I wanted to help protect them.

In the early 1990s, this research began through the pioneering work of Dr. Stephen Burnell and his collaborators. Exploring these remote lands, they discovered the significance of the Head of Bight as a calving ground and began what would become one of the longest-running southern right whale monitoring programs in the world.

They were adventurers as much as scientists – camping behind sand dunes for months, processing film in sleeping bags, launching a zodiac from a high-energy shoreline, and diving with whales to understand their behaviour. They lived off the land and sea, and they started something special. Something enduring.

At twenty-one, when I volunteered on this long-term research program, my life changed forever.

Nearly two decades later, I’ve now dedicated half my life to studying and protecting southern right whales. Like the whales themselves, I return to this coastline year after year. And every time, the place still captivates me and ignites my passion.

Southern right whales have returned to these waters for thousands of years to calve and rest.

After being hunted to the brink of extinction by commercial whaling, their recovery along Australia’s coastline became one of conservation’s quiet success stories. Science helped make that recovery possible.

For 35 years in the Great Australian Bight, researchers have documented individual whales using photo-identification. Each whale is recognisable by the unique pattern of callosities on its head – a natural fingerprint. Every photograph of a mother and calf becomes a data point, capturing identity, time and place.

Together, these images allow us to track whales across decades: where they go, how often they give birth, and how the population changes.

This long-term dataset is world-class and irreplaceable. It matters locally, nationally, and globally. It has been an honour to carry forward the legacy of this program, built by pioneering scientists who laid the foundations for marine mammal science and conservation in Australia.

Importantly, this science has never existed in isolation. It directly informs management and policy.

This research contributed directly to the establishment of the Great Australian Bight Marine Reserve in 1995 – now recognised as a world-leading example of a successful marine protected area.

For many years, the story for southern right whales was celebrated. Numbers had increased at close to the maximum biological rate. The marine park filled up. New calving habitats emerged along the coast.

It felt like proof that protection works.

Now, the story is changing – but not without hope.

Over the past decade, our data began to tell a different story.

Southern right whales were still returning – but not in the same way. Fewer calves. Longer gaps between births. A slowing of population growth.

This wasn’t just natural variability. It was a signal.

Our research drawing on more than thirty years of monitoring was recently published in Scientific Reports, and it shows that calving intervals have lengthened significantly since 2015.

For a long-lived species that reproduces slowly, this change matters enormously.

The cause isn’t visible from the cliffs or the close-to-shore whale sanctuaries across the southern coasts of Australia, where we travel in masses to view these gentle giants. To understand it, we must look far to the south.

Southern right whales feed in the Southern Ocean in subantarctic and Antarctic waters, relying on cold, productive, ice-influenced ecosystems rich in krill and copepods. That system is changing rapidly:

- Antarctic sea ice is shrinking.

- Marine heatwaves are becoming more frequent.

- Ocean productivity is shifting.

When prey becomes harder to find, female whales struggle to build the energy reserves needed to sustain pregnancy and lactation.

Effectively, what we are seeing on Australia’s coastline is the echo of change happening thousands of kilometres away.

This is why whales matter beyond their charismatic displays. They are sentinel species, living indicators of ocean health. When their reproduction declines, it tells us something fundamental is changing in the ecosystems we all depend on.

Awareness alone is not enough.

Marine protected areas and ocean sanctuaries are essential tools for managing threats, and Australia has shown what’s possible when protection is done well.

In Australia, mechanisms such as biologically important areas, marine protected areas, and the precautionary principle under the Environmental Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act (EPBC Act) provide pathways to manage threats and mitigate impacts from noise, vessel interactions, entanglement risk, ship strike and habitat disturbance.

But to prevent this decline from worsening, we must also tackle its root causes: climate change, pollution, and unsustainable pressure on food webs.

Incremental reductions in greenhouse gas emissions are not enough. To limit warming within the Paris Agreement’s guardrails – and to reduce risks to threatened species – we must achieve a significant reduction of greenhouse gas emissions, and quickly.

Acting now is the only path that offers a reliable future for species like the southern right whale.

At the same time, protection must extend beyond national borders. The Southern Ocean, and areas where these whales feed, need stronger and expanded protection from industrial fishing. Adoption of new marine protections through CCAMLR – the Convention for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources – is essential. The strong implementation of the High Seas Treaty will also be critical for safeguarding the ecosystems whales depend on for much of their lives.

Combined with ambitious action through international ocean governance and the global commitment to protect 30 per cent of the ocean by 2030, we have the tools needed for real change.

Marine protection must be meaningful.

Not just lines on a map, but real measures: protected feeding grounds, reduced pressure on krill fisheries, safer reproductive areas and connecting migratory corridors, and space for nature to recover.

Since 2022, Minderoo Foundation has been a cornerstone partner in the Australian Right Whale Research Program. This partnership has been far more than a research contract. It has been a shared journey of collaboration, discovery and purpose.

Together, we’ve contributed to more than twenty reports and peer-reviewed publications, directly informing ecosystem management, marine policy and national conservation strategies.

We’ve helped shape recovery planning, refine biologically important areas, and support expanded marine protection aligned with global 30x30 targets.

But the impact has gone beyond policy and publications.

Through community outreach, public talks, school programs, Indigenous partnerships and stewardship activities, we’ve helped build a broader, more inclusive conversation about ocean health.

This program has fostered careers, friendships and environmental leadership. The raw, harsh environment of the Nullarbor builds resilience and the bonds formed there last a lifetime.

We honour the partnerships with the Yalata Anangu community, the Department for Environment and Water, tourism operators and local communities scattered across hundreds of kilometres of remote coastline. There is a unique camaraderie among those who know life on the Nullarbor.

And there is still hope.

Australia’s southern right whale population remains healthier than some sister populations elsewhere in the world, where whales face devastating threats from vessel strikes, entanglement, disease and toxic algal blooms. Resilience is there, but it is not limitless. Our data grows more valuable with every passing year.

Our commitment to continue this work, for decades to come, is unwavering.

Our team – many of them women – leading through adversity, determined to carry this legacy forward.

Because, as we’ve seen: when science is at its best, it can create real change for marine life like the southern right whale and the ecosystems they depend on.

When a southern right whale surfaces, exhales, and lingers just long enough to meet your gaze, it feels personal.

Almost like an invitation. The whales are whispering to us through their movements and their changing rhythms. They are telling us that the ocean is changing, faster than we expected.

Listening is only the first step.

What matters now is what we choose to do with what we hear. By acting boldly, collectively, and with urgency, we can protect not only an iconic species, but the ocean itself and the life it sustains.

When the whales whisper, we must listen. And then, together, we must act.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Want to stay in the loop on our Natural Ecosystems, Gender Equality, and Communities work?

By signing up with your email, you agree to Minderoo Foundation’s Privacy Policy.