It’s been many years since I first strapped on a scuba tank, but I can still clearly remember those first glimpses of the underwater world off Noosa in south-east Queensland.

by Associate Professor Zoe Richards, Curtin University

What I saw on that early-1990s dive set me on the path to a lifetime of underwater exploration and study.

As an undergraduate marine biology student at James Cook University, I began to understand the staggering diversity of marine life and the remarkable complexity of ecological interactions that shape coral reefs.

Through my PhD years and into the 2000s, I had the chance to bring those ideas to life through my own fieldwork, witnessing thriving reefs firsthand in extraordinary and remote places such as the outer atolls of the Marshall Islands, Papua New Guinea, and the Andaman Islands.

I even had the chance to undertake biodiversity studies in places like Barrow Island before the marine environment was impacted by dredging and construction works, and remote parts of the Kimberley before the crocodiles started to expand their presence across the region.

Throughout those formative years and fieldtrips, I was continually awestruck by the beauty, diversity, colour and complexity of coral reefs.

I’ve had unforgettable moments with feeding manta rays and incredible interactions with bumphead parrotfish and napoleon wrasse, and close encounters with sharks and huge grand-daddy tuna.

As a coral biologist, some of my most unforgettable moments have been discovering new coral species or spotting coral-mimicking algae. I’ve loved learning how gall crabs shape coral branches to make cozy little breeding chambers and figuring out how red-pigmented corals in shady spots modify and redistribute light to help their symbiotic algae undertake photosynthesis.

All these moments have reinforced for me just how diverse and magnificent corals and the animals that live in and amongst them really are. These lived experiences have fuelled my passion to share the beauty of the reef with others.

I’ve always believed that we protect what we love, and I hold onto the hope that, through my work, others can come to see the reef as I have and be inspired to protect it too.

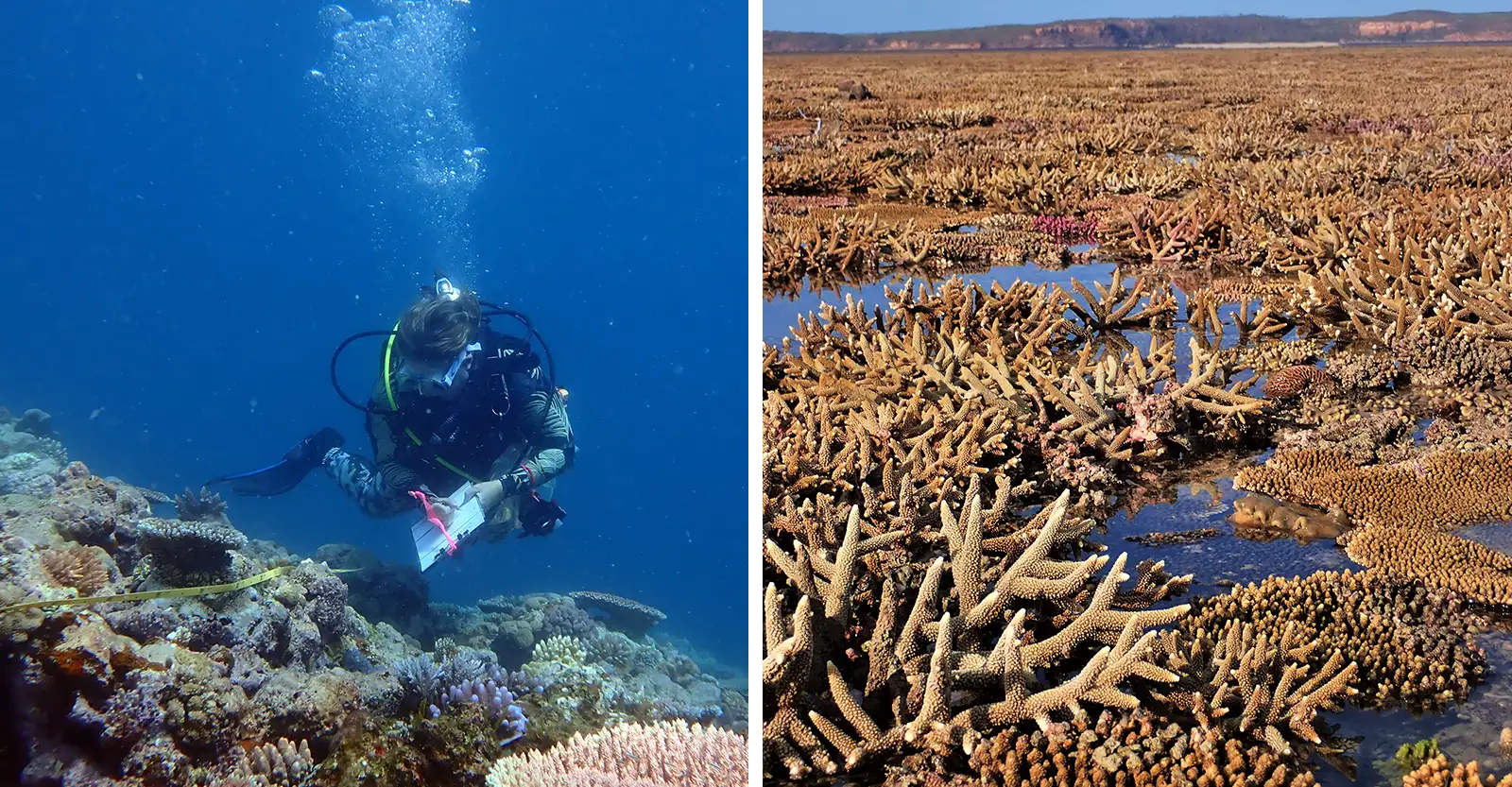

But these days, my return trips to the reef often feel more like difficult reunions than joyful homecomings. The reefs I once knew are disappearing right in front of me.

I’ve caught myself slipping into the past tense when I teach my second-year marine ecology students, saying things like “Scott Reef used to be the jewel of Western Australia’s reef systems,” or “Ningaloo used to have the most incredible, lush coral gardens just metres from the shore.”

It’s an uncomfortable truth, but climate change is putting Earth’s life-support systems at risk, and coral reefs are among the most vulnerable.

This year, up to 60 per cent of the corals in the northern Ningaloo Reef lagoon died because of the 2024/25 heatwave, which was the most severe and extensive heatwave ever to impact Western Australia.

I increasingly struggle with the thought that my youngest child, who’s not yet old enough to swim in open water, and my future grandchildren may never have the chance to see coral reefs as I have been fortunate to do. It pains me to imagine that they might never feel the joy of immersing themselves in a wild ecosystem so vibrant, healthy, and teeming with life.

When I reflect on the future of coral reefs, a phrase I think about a lot is “Don’t accept what cannot be changed, change what you cannot accept.”

I have come to realise that in many ways, climate change comes down to the choices we make. I hope that, as a global community, we start making smarter, broader, and genuinely meaningful nature-positive, Real Zero choices, because the window for doing so is closing very fast.