A world-first open-access database that maps research on plastic chemical exposure and human health impacts, providing policy, governance and scientific insights.

About the plastic health map

The first ever Plastic Health Map collates research that measures the potential human health effects caused by a wide range of plastic chemicals.

In the absence of health monitoring for these plastic chemicals, the Plastic Health Map shows what has been studied over several decades and is a tool to help us transition to a world where plastic is more sustainable, safer and free of toxic chemicals.

It brings together data from more than 3,500 primary studies from 1960 to 2022, which can be explored by researchers, clinicians, policymakers and anyone keen to find out more, via a user-friendly dashboard.

Evidence focuses on plastic polymers, bisphenols, plasticisers, flame retardants, and per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS). Users can search by chemical or health outcome, in different countries, age groups and more.

The methods and results of this systematic evidence mapping project are published in the Environment International article.

Key findings

1. There are significant gaps in research on how plastic materials affect human health.

- Of more than 1,500 chemicals mapped, less than 30 per cent have been investigated for human health impacts.

- Many human health outcomes have not been investigated for any given chemicals class.

- No human exposure studies screened in the time frame of this project looked at the health impacts of micro- and/or nanoplastics.

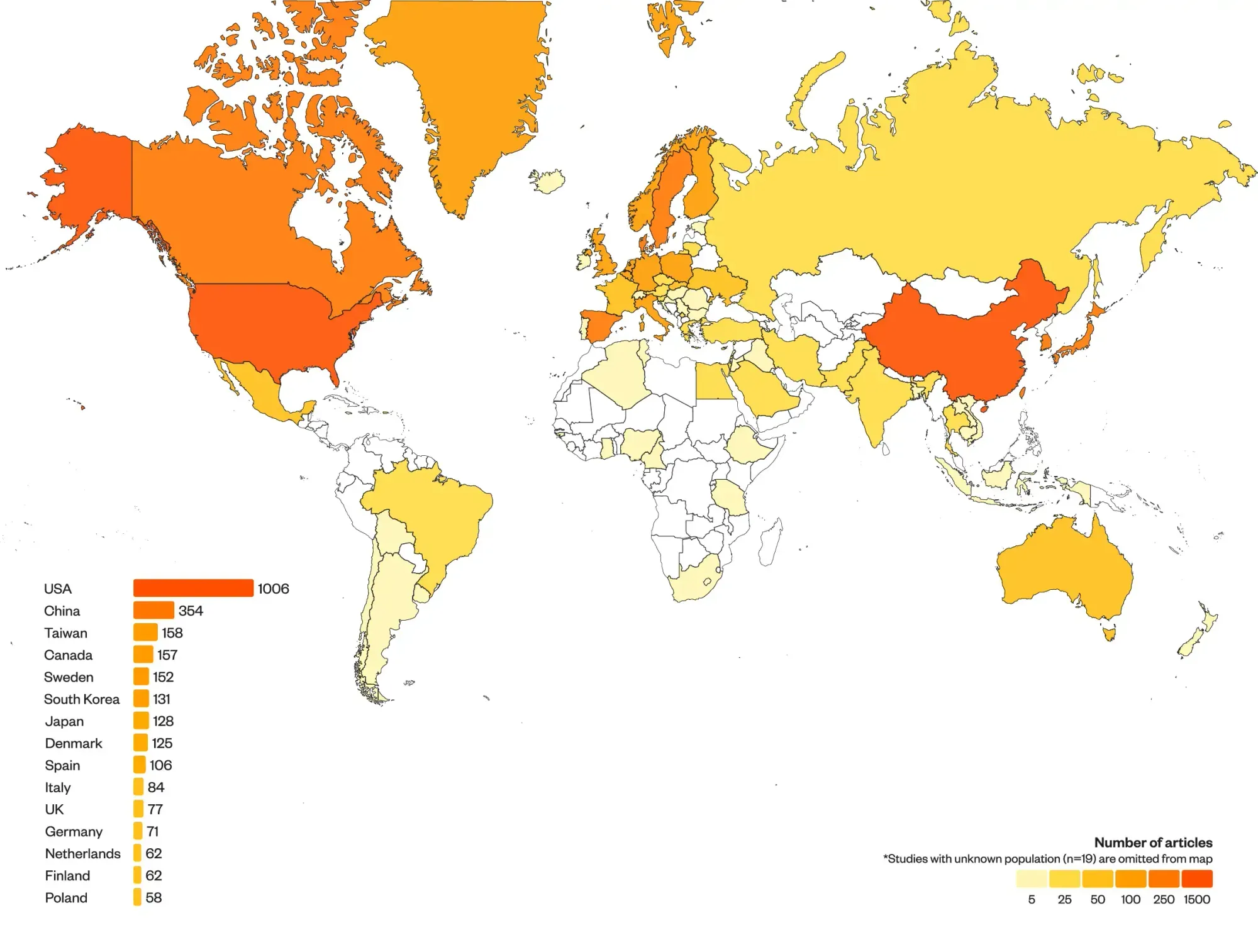

- Very few studies were conducted in low-income countries.

- Limited studies focused on older/elderly populations.

- While more than 1,000 studies looked at the effects of mothers’ plastic exposure on children, no studies were carried out on the health of children whose fathers have been exposed to plastic chemicals.

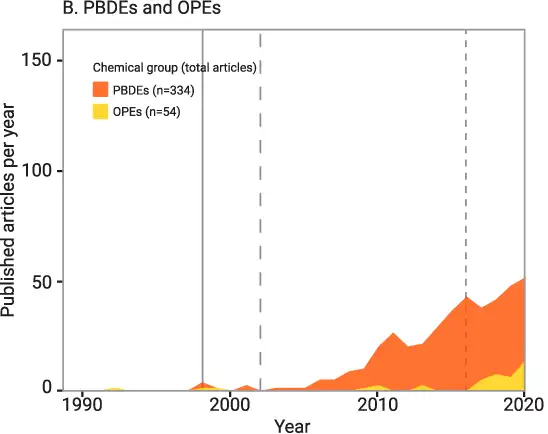

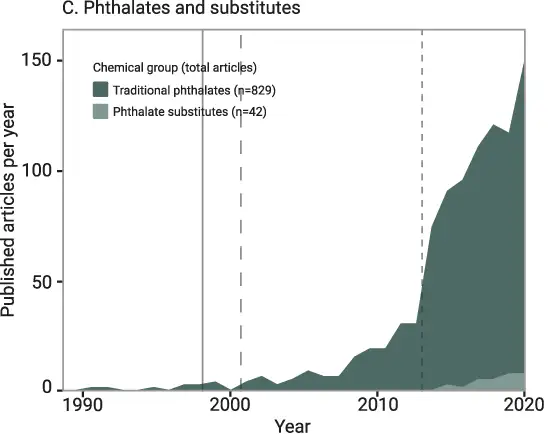

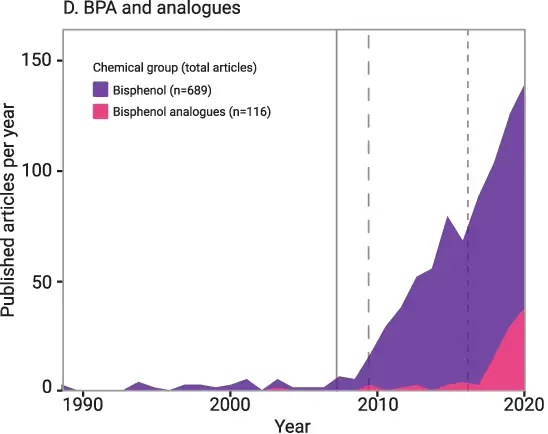

2. Studies on health impacts of substitute chemicals commence many years after introduction.

As plastic chemicals proliferate, regulation struggles to keep pace with the quantity and complexity of determining their health effects. Restricted and banned chemicals are often replaced by structurally similar substitutes with the same or other unknown hazards. Only a small number of studies investigated these.

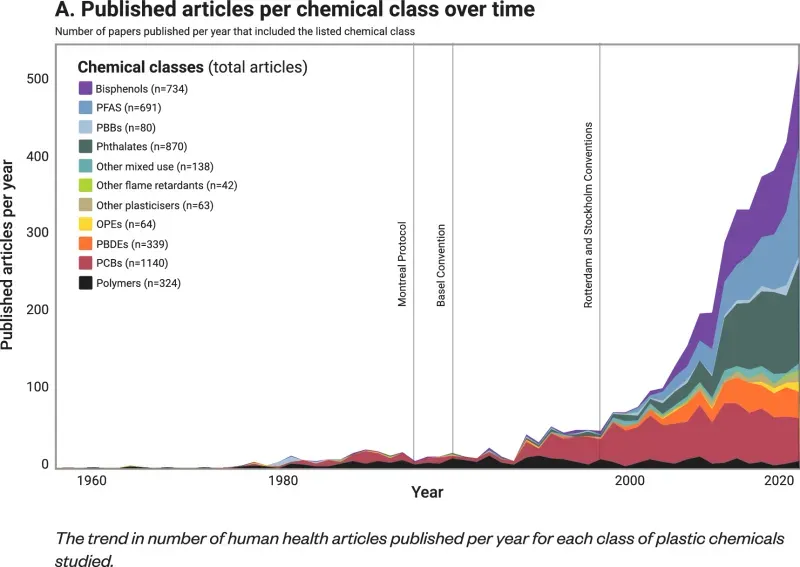

Trend in number of health articles published per year for classes of plastic chemicals banned/restricted and their substitutes.

In each plot, the vertical lines from left to right indicate first ban/restriction of original chemicals, the rise in use of substitute chemicals and the rise in health articles published on substitute chemicals, respectively.

Trend in number of health articles published per year for classes of plastic chemicals banned/restricted and their substitutes.

Explore the data

The Plastic Health Map is an open access tool for researchers, policymakers and interested citizens on the state of human health research and plastic chemicals exposure. It provides important insights for policy, governance and further scientific enquiry.

Data overview

Data overview

What is the Plastic Health Map and why is it important?

The Plastic Health Map is an open-access, interactive systematic evidence database collating human health research on a wide range of plastic chemicals from several different chemical classes, published between 1960 and 2022.

The database includes interactive plots and heatmaps showing the number of articles published each year by plastic chemical class, individual chemical, category of health outcome and the geographical distribution of the studies.

The plots and heatmaps can be filtered by plastic chemical, health outcome category, year of publication, study design, population (including country), age group and general/special exposure risk. Article references can be viewed and downloaded based on the filters selected.

Where can I learn more about the study behind the database?

The journal article published in Environment International provides background information, details on our study methodology, a comprehensive overview of the database, as well as detailed discussion of the results identified by the study. Additional supplementary data is downloadable directly from the journal’s website. Our project and relevant updates can also be found on our OSF page.

Did the study look at all the plastic chemicals?

It is estimated that there are more than 10,500 chemicals used in plastic production and only a fraction of these have been studied for human exposure and health outcomes. We conducted a targeted search for 1,557 chemicals categorised as polymers, bisphenols, per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) and plastic additives functioning as plasticisers and/or flame retardants. The Plastic Health Map houses the entire searchable database of included chemicals, indexing the multiple synonyms and commonly used terminology describing these chemicals.

I’m having trouble connecting to the database – what can I do?

We recommend using Chrome or Microsoft Edge. If you have trouble connecting:

- Check your browser’s security settings – you may need to delete cookies that have been saved.

- Check that the beginning of the URL starts with “https” (not “http”).

The figures (heatmaps and plots) in the map look crowded/squashed on my screen – how can I fix this?

First, the map is best viewed on a full computer screen with the browser window “maximised”, rather than on a mobile device. Second, the “squashed” issue is related to the web-browser settings and can be fixed using the zoom function under “settings”. Try reducing the zoom gradually until the figures present properly without overlap/squashing of text and images (80-90 per cent may be suitable when using a large monitor; 67 per cent on a small laptop).

Why are microplastics and nanoplastics (that is, plastic particles) missing from the Plastic Health Map?

Despite including micro- and nanoplastics in our search strategy, just one study screened during this project measured microplastics in human tissues and analysed relationships with health outcomes. As it was the only study measuring the plastic exposure in faeces, this study is not represented in the Plastic Health Map but is described in our paper. We are aware that further studies on particles may have been published since January 2022, and these will be represented in future updates.

How should I reference the database in my projects or publications?

Please cite our Environment International article and the Minderoo website when referencing the Plastic Health Map.

What are the limitations of the database?

The scope of the chemicals in the Plastic Health Map is limited to polymers, plasticisers, flame retardants, bisphenols and PFAS, although we recognise that humans are potentially exposed to many other plastic chemicals. There is potential for the database to include others. Due to time and resource limitations, only articles published/available in the English language are included in the database.

While we indicate whether studies involved male/female or mixed sex populations, for mixed populations we do not provide details on any sub-analyses that may have been conducted on male/female groups.

The map does not display the correlations found/not found between plastic exposures and health outcome measures. We followed the typical systematic evidence map framework to demonstrate the scope of research conducted to date, without assessing the quality of studies, which would be necessary to report on correlations.

Who can I contact for questions and suggestions regarding the database?

We welcome questions, feedback and collaboration on this project.

Contact: PlasticHumanHealthReviews@minderoo.org.

Creators

The Plastic Health Map was created by Minderoo Foundation, in collaboration with Australian research institutes:

Bhedita Seewoo [a,b], Louise Goodes [a,b], Louise Mofflin [a,b], Yannick Mulders [a,b], Enoch Wong [a,b], Priyanka Toshniwal [a,b], Manuel Brunner [a,c], Jennifer Alex [a], Brady Johnston [a], Ahmed Elagali [a,b], Aleksandra Gozt [a], Greg Lyle [d], Omrik Choudhury [a], Terena Solomons [e], Christos Symeonides [a,f], Sarah Dunlop [a,b]

[a] Minderoo Foundation

[b] School of Biological Sciences, The University of Western Australia, Australia

[c] School of Molecular Sciences, The University of Western Australia, Australia[d] School of Population Health, Curtin University, Australia

[e] Health and Medical Sciences (Library), The University of Western Australia, Australia

[f] Murdoch Children’s Research Institute, Royal Children’s Hospital, Australia

Acknowledgements

Gratefully acknowledging valuable contributions from:

Emily White, Tristan Dale, Hamish Newman, Delia Hendrie, Alina Naveed, Andrew Lowe, Mark Norrett, Matthew Cantrell, Megan Bakeberg, Anastazja Gorecki, Jane Edgeloe, Akila Yapa, Elizabeth Thomas, Joanne Webb, Lisa Hooyer, The UWA Library, Allan Finn, and Julie Glanville.

Get in touch

We welcome questions and suggestions regarding this research reach out here.